At troubled times like the present, it’s worth reflecting on how great minds of the past managed to relax and clear their minds.

Minds do not come much greater than the Victorian physicist and mathematical duo of James Clerk Maxwell and George Gabriel Stokes. During the day, they worked tirelessly to put in place the physical principles and mathematics they needed to build the earliest classical field theories.

But when it came time for recreation, they did what any red-blooded Victorian gentleman would do, and threw cats out of the window.

This is Maxwell explaining this activity to his wife (who appears to have heard stories and may have been asking for reassurance that she hadn’t married a maniac):

There is a tradition in Trinity that when I was here I discovered a method of throwing a cat so as not to light on its feet, and that I used to throw cats out of windows.

I had to explain that the proper object of research was to find how quick the cat would turn round, and that the proper method was to let the cat drop on a table or bed from about two inches, and that even then the cat lights on her feet.

(The Life of James Clerk Maxwell with extracts from his Correspondence, letter, 1870 p.599)

Stokes’ daughter also wrote about it, though she made it sound rather less pleasant for the cat:

He was much interested, as also was Prof. Clerk Maxwell about the same time, in “cat-turning”, a word invented to describe the way in which a cat manages to fall upon her feet if you hold her by the four feet and drop her, back downwards, close to the floor. The cat’s eyes were made use of, too, for examination by the ophthalmoscope, as well as those of my dog Pearl: but Pearl’s interest never equalled that of Professor Clerk Maxwell’s dog, who seemed positively to enjoy having his eyes examined by his master.

(Memoir and Scientific Correspondence of the Late Sir George Gabriel Stokes, Humphrey, 1907)

Stokes and Maxwell were intrigued by a question from physics: how does cat manage to turn itself around without violating the conservation of angular momentum?

After all, it starts off upside-down and rotates until it lands on its feet. Surely this required some angular momentum from somewhere? The prevailing assumption in the 19th century was that the cat must be using some kind of “push off” from the dropper’s hand.

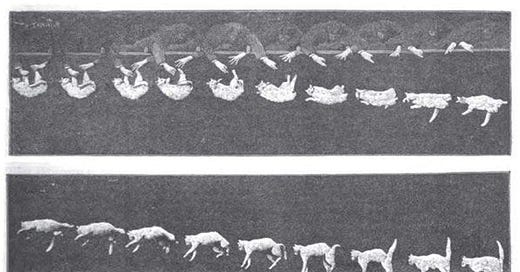

However, pioneering high speed photography from Étienne-Jules Marey (1894) showed that this was not so: there is no initial rotation in a dropped cat.

(Nature, 18941)

Marey’s photographs showed what was happening, but just deepened the mystery: the cat started with zero initial angular momentum, and it rotated itself within fractions of a second to land on its feet. It’s a fundamental law from Newtonian physics that angular momentum is always conserved, so how was this rotation achieved? Several remarkably influential papers over the course of the 20th century went progressively deeper into analysing the phenomenon:

L. Lecornu, 1894: Suggested (basically correctly) how the rotation was possible while maintaining zero net angular momentum

G. G. J. Rademaker and J. W. G. ter Braak 1935: Advanced on Lecornu’s solution with a simple two cylinder model that they matched qualitatively to photographs

T.R. Kane and M. P. Scher, 1969: Gave a more detailed analysis and added computer analysis to overlay idealised solutions on some beautiful photographs (see below)

R. Montgomery, 1993, Gave more general solutions, showed that Kane and Scher’s solution is the most efficient, and nailed down some surprising links to gauge theories in physics.

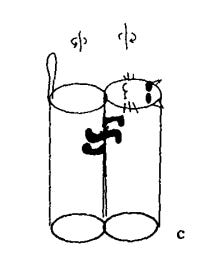

The physics is quite intricate. The basic answer that Lecornu described and then Radenaker, ter Braak, Kane and Scher filled out, is that the cat keeps its total angular momentum at zero at all times by bending its body sharply, and then twisting the each half on two axes that combine to cancel out the rotation of the whole.

However, while this motion is straightforward enough to set up in differential equations, it is almost impossible to explain in words. One of the more popular non-technical ways of “getting it” is Wikipedia’s animated gif, but far clearer (at least to my mind) is Montgomery's old-school approach: a hand-drawn cartoon.

One reason Montgomery’s explanation is so clear is that he chooses to examine an “extremified” twisting path that separates several stages of motion and shows them in isolation. This gives clarity at the expense of a realism — a common trade-off in idealisation in physics. (Also, his cat appears to be wearing sunglasses, but to the best of my belief this is not essential either).

First stage: folding up — (zero angular momentum because both half are moving in opposite directions):

Second stage: rotate each half in opposite directions — (zero angular momentum because you have two equal halves rotating opposite to one another)

Third stage: unfold — (zero angular momentum for the same reason as the first stage)

(To repeat, this process is an extremised example which serves to show that rotation is possible while maintaining zero total angular momentum throughout. It is not something a real cat could do: its back would break. A real cat combines incomplete stages into one another, and circumvents the need for a full 180 degrees fold.)

If this isn’t confusing enough, Montgomery’s paper then ups the ante further by showing that the cat’s twisting motion has a deep connection to gauge theory.

To do this, Montgomery reformulates the problem in terms of a “space” of shapes that the cat can adopt, relates this to the overall configuration space for the cat, and imposes a condition that constrains the total angular momentum to zero. He then shows that the reachable states give him a gauge situation (with the anholonomy being the overall rotation of the cat in physical space) and then — apparently for fun — shows that the optimised solution for reaching any given orientation is equivalent to the equations of motion for a charged particle travelling on the projective plane under the influence of an axially symmetric magnetic field and metric.

Which is all quite a surprise. But it brings us back — via a small a diversion — to Maxwell and Stokes’ day jobs: gauge theories built on their field theoretic foundations formed the basis of some the most successful and influential theoretic work of twentieth and twenty-first century physics.

Palate cleansed? Mind cleared? Cat thrown out of the window? Excellent. Back to the real world it is.

Photo sequence reversed (by me) from Marey’s original in Nature, because it originally ran from top right to bottom left - a confusing orientation for a Western audience.

Thank you, that was great fun and very clear. I’ll share with some other ex-physics friends :)