Unexplained excess deaths in the UK - have they stopped?

There was a clear pattern of excess deaths from June 2021 to December 2022, beyond those attributable to COVID. What's happening now?

There are a bewildering number of ways of calculating excess deaths for a country: the number of deaths in addition to those you’d expect in normal times. There’s no better entertainment for the slightly morbid geek than to debate alternative methods of trending patterns, seasonality, age-standardisation, registration and occurrence dates and delays.

But for a while now in the UK, we’ve been able to shelve these debates, because it really hasn’t really mattered what method you used. All of them said the same thing. From about July 2021 onwards, there were about 80-100 more deaths every day than you’d expect, even after accounting for COVID.

That’s a lot, by the way. A useful number to have in your head for deaths rates is 25. In most Western countries like the UK, you’ll see a touch under 25 deaths per day per million. So for England + Wales (the most common data-cut we have) that makes about 60 x 25 = 1500 deaths a day. They’re higher in the winter, lower in the summer. So to have consistently 6-7% more than that over an 18 month period is worrying.

Here’s a very, very simple way of showing this excess that cheerfully ignores all the subtleties that I mentioned above. Grab the occurrences tab (16a & b) of the ONS’ weekly provisional death counts for England and Wales, take the difference between 2020-2023’s deaths to the five-year average, subtract the ones due to COVID, and show the resulting count - in this case charted with a 28-day rolling average, because it’s a noisy ride.

Note, this pattern could be distorted by patterns in age-profile, trends, and other subtle effects, but … honestly … it isn’t. Those who take the time and care to make all those important adjustments (god bless ‘em), find the same grim pattern.

What’s killing 80-100 people a day?

To absolutely no-one’s surprise, there have been loud and determined efforts from some quarters to assert that vaccines are to blame for this higher death rate. But as well as the obvious mismatch to timing, to age-profile and to mechanism, it’s easy to show directly that this is wrong - in fact, that it’s reverse of the truth. Most simply, this can be done by splitting age-adjusted mortality rates by those who have had a vaccine and those who have not (the vaccinated being counted from the instant they received their first COVID jab).

More plausible theories include the deaths being down to unrecognised and undiagnosed effects of COVID, including longer-term sequelae, or to missed diagnoses (e.g., of cancer and heart disease) during lockdown, or to the long-term effects of austerity on the most vulnerable in the UK.

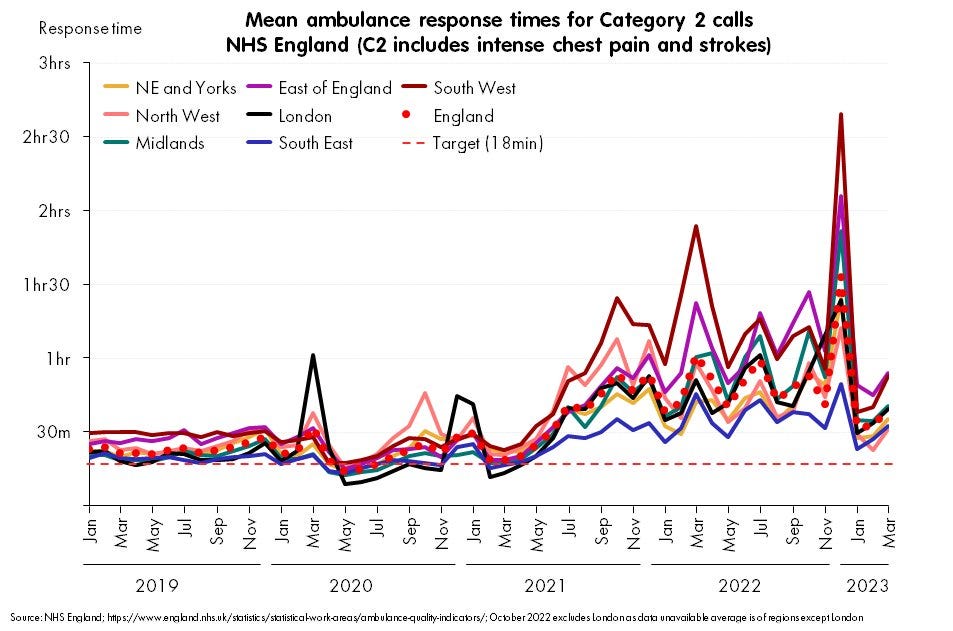

But the largest factor - in my view - is likely to be the degraded state of the NHS, especially in emergency care. One indicator of this is ambulance response times, which certainly temporally match the start of the excess deaths, though of course this is not proof that they are the cause: correlation does not imply causation.

Even the suggestive observation that the South West region has the highest 2022 excess deaths levels, does no more than add a touch of plausibility to the theory: causation can go in many directions in such a complicated situation (and this correlation does not hold everywhere: e.g., the East of England has the second-longest delays but relatively small excess deaths).

More solidly, causal links between emergency care delays and deaths have been provided by patient-level analysis such as this paper in BMJ’s Journal of Emergency Medicine; and using these rates, a group of actuaries (the heroic COVID-19 Actuaries Response Group) have estimated that this effect may indeed be of the order of 60-70 deaths a day in the second half of 2022 - that is, the majority of the unexplained effect.

So, why hasn’t it started getting better?

But this theory has a challenge, which is already obvious from the right hand side of that ambulance chart. The situation in emergency care radically improved after the first few days of January 2023 - and we can be this precise because we have daily data for ambulance turnaround times, which suddenly fall like a stone. So while NHS emergency medicine has not recovered, it has also not even approached the disaster of the last few months of 2022. It’s more like June 2021.

So excess deaths should have fallen away, right? At least a bit? Causation is not sufficient for causation, but surely - at least at this level - it should be necessary?

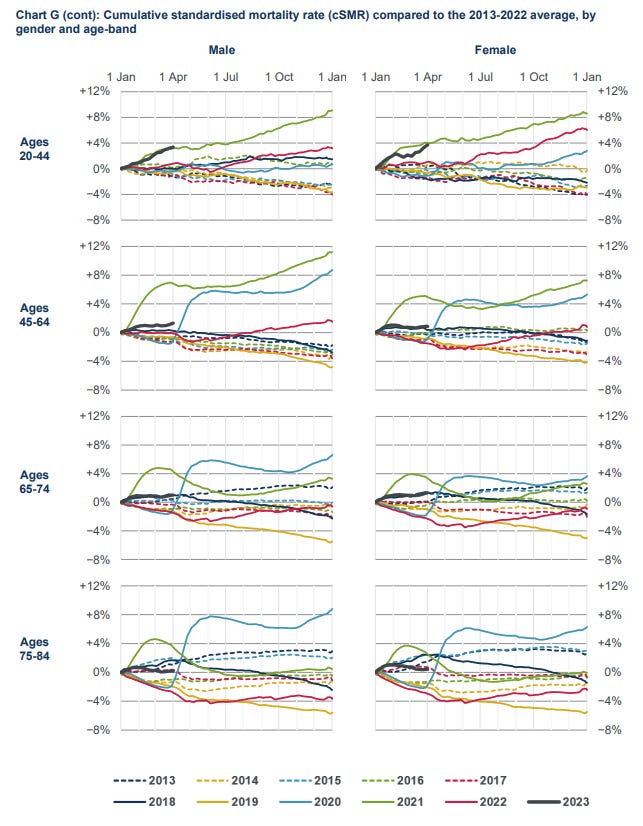

It absolutely should be, so I’ve been very surprised to see careful analysis from bodies like the Continuous Mortality Investigation showing excess mortality continuing to rise in January 2023, even as the pressure lifted on emergency departments across the UK (this chart and the next from their quarterly analysis update).

So, maybe … it’s not NHS pressure after all? Perhaps this NHS pressure was caused by the same (unknown) cause as the excess deaths - hence the former temporal association - and while the NHS has started to manage it better, the underlying cause continued to kill people?

Has it … in fact … started getting better?

I suspect the above is wrong. I think these non-COVID excess deaths have fallen sharply in early 2023, and we’re being misled by registration delays, along with a bunch of holidays, flu, and general winter chaos.

The key point to realise is that (almost) all ONS analysis, the CMI analysis and most other data we can access is based on registration date - when the death was registered, versus when it occurred. The issues with this are obvious: registry offices are closed on Sundays and public holidays, and some deaths (particularly in the youngest) cannot be certified until a coroner’s report has been completed, which can be months later.

However, registration counts have the massive advantage of being available quickly, and never changing retrospectively - and since most of these problems aren’t that bad and average out over time, they’re a much more convenient count and give the same answer.

Most of the time.

Look again at CMI’s cumulative counts for Q1 2023, now cut by age. There’s some cumulative excess in all ages, but the most is in the youngest.

Notably, the youngest are exactly where delays are longest, so one could suspect that what we’re actually seeing is some of the spike of deaths in late 2022 “spillling over” and being registered in the early months of 2023. If this is right, then we have the possibility that excess deaths really did fall precipitously just at the same time that the pressure lifted on the NHS.

Since this is so nakedly being led by a hypothesis, it would be good to put a bit more weight behind the suspicion. So let’s do that.

Mining deep into ONS data tabs

The ONS are well aware of the problem of registration vs occurrence date, and in recent years have quietly included a model-based estimate of deaths by occurrence in their weekly updates. Given how many deaths have been registered so far occurring in a particular week, and the past pattern of registration delays, the model estimates how many it would expect to see when all registrations are complete. If it worked, this model would give us the best of both worlds: immediate and timely estimates of the deaths by occurrence date.

But does it work? The predictions of this model have been published for a while now, we can track the performance of this model over time (i.e., how its week -1, week -2, week -3 estimates compare with the final count).

So, the short answer is that the model is pretty useless at getting the answer right for the most recent week, it displays a big, but inconsistent undershoot, and it’s still pretty flaky at week -2 and -3. But for week -4 and more it’s fairly solid, getting the answer right to within 2% or so. So let’s cut off the three most recent weeks, but tentatively trust it on for the rest.

What does it tell us?

Well, when you push the model’s weekly estimates (minus three) into the earlier simple count-minus-average-of-previous-years-minus-COVID calculation (the same rough calculation we started this post with), and then zoom to see what happens at the start of 2023, where - remember - ambulance delays abruptly improved after the first week of January … you get this.

The dates are the “week ending” so - again, the timing is at least suggestive.

Now, I should be very clear, this could well be very wrong. All the age-mix effects that I’m not correcting with age-standardisation, all the trends, and especially all that winter chaos of flu spikes in 2023 and the benchmark years: they’re all very important and very real. It is fiendishly difficult to disentangle all the effects, and I have not done nearly enough to do so.

But my hypothesis is that when people more careful and smarter than me age-standardise and fully adjust their analysis of deaths by occurrence date they will find this same sharp cliff-edge of excess deaths in the second week of January 2023, followed by a gentle slope in March and April back as NHS capacity comes under gradually increasing pressure again. What you’d expect if this capacity limit were a major causal factor in those deaths.

Also note that even if all this is correct, it only makes the hypothesis consistent with the evidence. It still does not prove that NHS pressure is the major factor behind the deaths. Flu (and RSV, and COVID) also dropped precipitously at the end of 2023 - in fact that’s why the NHS pressure came off. If any of those (or other factors, like weather) are major drivers of the excess, we’d see a similar pattern. The emergency care hypothesis remains just that: a hypothesis.

If this is right, what next?

The NHS, and in particular, NHS emergency medicine has not been fixed. It is just under a little less pressure right now. If the current patterns continue into summer, we should expect that 2023 will see some, but lower excess deaths than we saw in 2022 or the second half of 2021. That is, if the NHS pressure from a few waves of COVID plus trying to catch up on elective surgery doesn’t get too much worse, then we should see longer term excess death levels coming back up again in April, but bumping along at around 50 or fewer per day, rather than the 80-100 we’ve seen in 2021-2022.

But then, if we get another emergency care collapse like we did in December 2022, we should expect to see another horrific spike of deaths. While some of these will likely be directly attributable to whatever causal factor triggers that collapse (December 2022 was driven by a flu spike on top of a COVID peak with a side order of RSV, for example) the tragedy is that we can expect further excess deaths as well, which could be attributed to the collapse in timeliness and availability of care, even for those who would otherwise have lived.

Notes: @Jean__Fisch’s display of effects of delayed registration have been fundamental to some of the thoughts here. @ActuaryByDay and @AdeleGroyer’s work have been invaluable in building my understanding, though I have no reason to believe that any of these people will agree with all (or any) of this post. All mistakes, naivety are mine.

The ONS model of ‘expected’ occurrences scares me. I know it is being held in place by the distant past data, but the bias in 0 to -6 is never what you want to see. Likely there needs to be a different kernel or kernel break for the more recent values. Uncertainty should be massive as we work towards the present, but the having the error diverge is a recipe for misuse