Before we get into the meat of this, a quick recap. If you’ve read previous run-downs on the patterns of excess deaths in England and Wales, you can just skim the next three paragraphs. If not, do plunge in - it’s as condensed as I can make it.

Previously, on Excess Deaths…

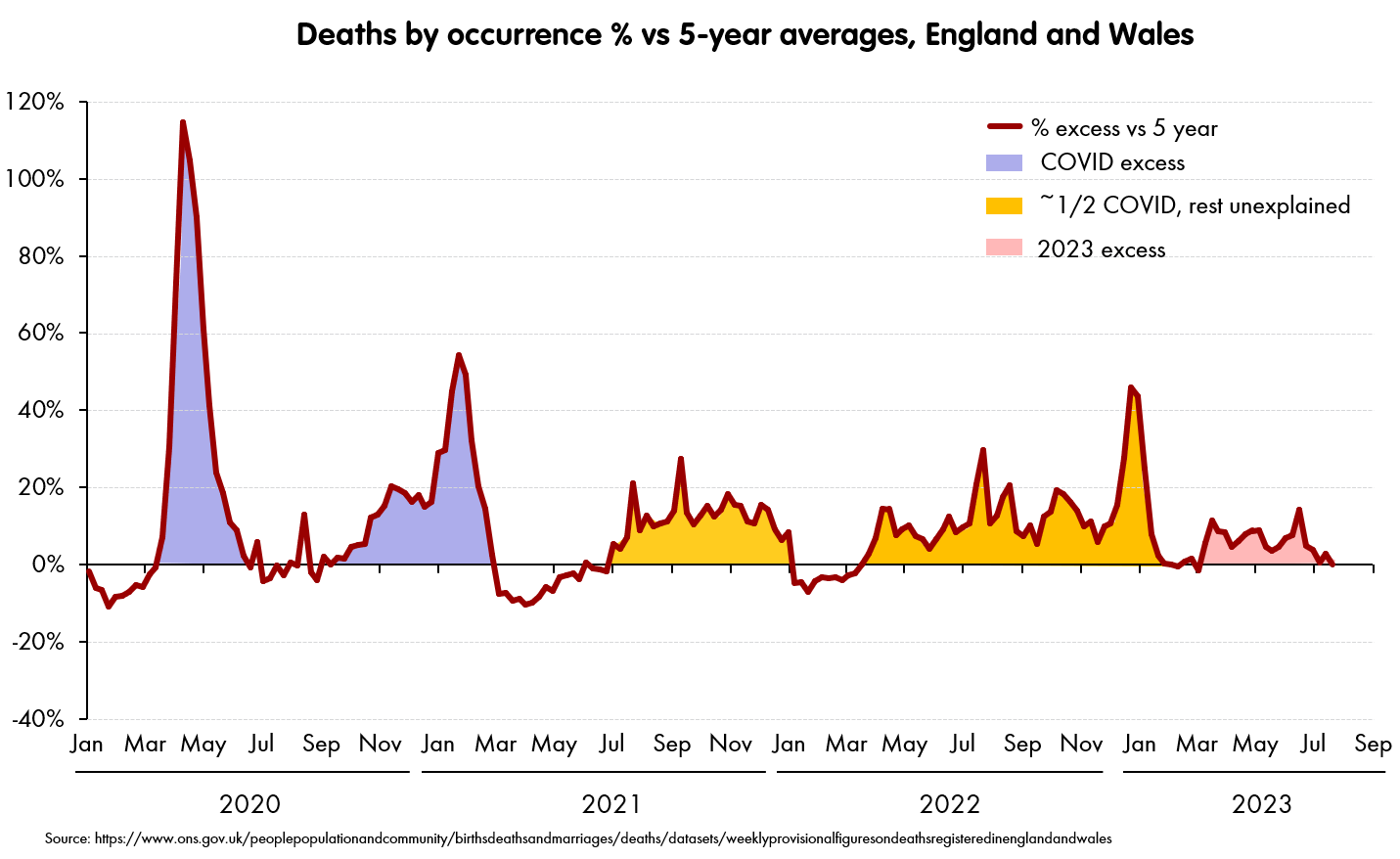

Excess deaths are the difference between the observed number of deaths in a period, and the expected number. Many people can (and do) disagree on how to construct the “expected” number, but once you do, they give you a net measure of mortality from all causes. Here’s a simple count version with the “expected” being simply the average of the previous 5 years (ONS standard).

As far as the pandemic and post-pandemic years are concerned, pretty much everyone agrees we got a couple of big spikes from COVID in 2020 and the winter of 2020/1 (the second considerably blunted down because the usual winter flu was absent) followed by a bit of mortality displacement in the spring of 2021 (i.e., people who would otherwise have died were already dead).

Everyone then agrees that the excesses started again sometime ~May/June 2021 and then persisted pretty consistently for the rest of 2021 and all of 2022 (except for another winter “flu shadow” in Jan-Mar 2023), and then ended in a spectacular spike in the last couple of weeks of 2022.1

Plenty of people disagree on why these excesses are happening, but we are at least pretty much in agreement that they’re significant and real.

… and now this week’s episode

We get a little bit of controversy as we head into 2023.

Simplifying enormously, the question is whether the excesses are now continuing at similar or even higher levels to 2021/2022, or whether they’re much lower - hardly more than those attributable to COVID alone.

There are differences in choice of baseline (2019 or 5-year averages) and on adjustment for age (you really should), but the most important difference is between those who are using deaths by registration date, and those who are (trying to) use deaths by occurrence date.

The below chart is from Jean Fisch, who has been making adjacent arguments to those in this post over on the site-formerly-known-as-Twitter, and his charts of cumulative excess deaths (i.e., the in-year integrals of the chart above) are beautifully clear: the best way of showing the delta that I know of:2

In previous posts, I (and Jean) have argued that a big chunk of the “spike” in deaths at the end of 2022 has been artificially “pushed” into the first month of 2023 by long delays in registration, thus misattributing to 2023, excess deaths that had occurred in 2022. But - as Jean points out - there is also an ongoing difference in 2023: the ongoing “slope” of the cumulative blue line is also very different.

The reason for this difference is simply that - as far as I can ascertain - there has been somewhat of a collapse in the ability of England and Wales’ systems to register deaths in a timely manner, and the system is now in an uneven process of recovery. As a result, those calculating deaths by registration date are mostly counting the ebb and flow in the backlogs of death registration, and not the difference in contemporary death rates that they think they are.

If this is right, then - unfortunately - it includes authoritative sources such as the Continuing Mortality Investigation: a programme set up and run by the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, which is closely watched by everyone monitoring national mortality risks.

Delays have been getting worse, but that’s not always so bad

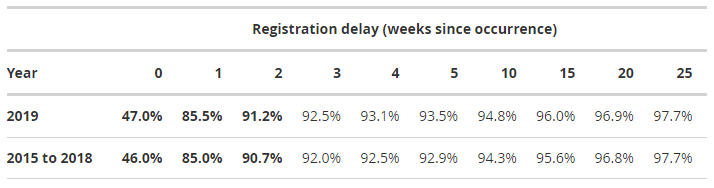

To motivate this, let’s look at the last time the ONS published a report on registration delays, which was fairly recently: April 2023. Unfortunately - and this is the central problem that bedevils all of this analysis - you have to wait until the registrations can be judged to be complete before you can fully understand how delayed they are. So the report in 2023 only looked back to the end of 2021. Any more recent, and how would you know whether there were a few more deaths yet to come in?

But even with such an early cut-off date, the issue was already looming:

Very simply, far fewer deaths were being registered in a timely manner. There were a variety of reasons for this, including resource, delays in coroners’ courts and - in the pandemic years - the sheer number of deaths to be processed. And the ONS investigation showed that these longer periods were universal across causes of death, and across all regions of England and Wales.

Now, in fact, this is still tolerable. So long as the delays are fairly stable over time, then tracking registration date still gives a reasonable track of what is going on (albeit with some “smearing out” and “time-shifting” of sudden rises and falls). And the ONS used these patterns to go further: they built a model to predict final death counts by occurrence date from the registration counts at particular time points. Outputs from this model is what I used to build the first excess deaths chart in this post. It’s actually being proved pretty accurate, so long as you chuck out the most recent couple of weeks (which I did).

So, if the delays were merely long (as they are in 2021) but also stable, then we might still be OK. The registration date analysis would need to be read with some allowance for the delay effects, but it would give broadly the right patterns and trends. And if you wanted to do better, you can use the ONS model to correct for that - with the allowance that it’s just a model.

A direct look at registration “catch-up”

The much more difficult issue comes when delays between occurrence date and registration date are not constant, but vary dramatically. There are a variety of ways of showing that this could be happening, but the most direct is to look at ONS’ monthly summaries of deaths by occurrence date (unfortunately, they do not release these weekly).3

Each release includes all the deaths registered up until the 7th day of the following month,4 so you get subsequent releases showing something like this (or, for the four most recent releases, exactly like this).

That is, you get a new chunk of deaths for each of the months being covered, but with a sharp drop-off at the end of the month - most of them haven’t been registered yet. So the subsequent release has new deaths “topping up” the previous months, as well as adding the month under question.

So, one metric to illustrate the chaos in registrations is pretty simple. For each new (monthly) release, what is the proportion of newly registered deaths that actually relate to the month in question, versus the number that relate to historic “catch-up”. I.e., what is the ratio between the red in area A and the red in area B.

If we look historically from numbers in the ONS “delays” report, then in the case where the registration backlog was fairly stable, then that the line should be fairly stable at around 8% (i.e., (1-92.5%)/92.5% ~ 8% from the 4 week value) of the deaths each month should be from “catch-up” deaths from previous months - with remaining “true” deaths from the month in question). It’ll wobble a bit as we work our way through both historical and current spikes in excess deaths, but it’ll wobble somewhere around that value.

There are some quibbles (again) about what happens to this ratio when deaths rise or fall suddenly, but let me plot the value, and it might become clear why I haven’t worried too much about that.

The level is not even the biggest problem - it’s the variability, and in particular the jumps we get in 2023: we have had months where over a quarter of the monthly death registrations have been from catch-up from historical months. And then the next month this drops down to 16%, and then comes back even higher. A monthly variability of ~10% of the total numbers we are trying to analyse.

One scenario that’d give variability in the “catch-up factor” is literally that: a period of “catch-up” in registrations. That is, a historical death backlog suddenly being “poured” into the monthly registration figure and giving an artificially high reading. A +-10% spike is more than enough to swamp any excess death signals we’re looking for. There are other scenarios that could make these numbers change too (including - somewhat paradoxically - the system slowly falling even further behind) but these are likely to give less variability in the figures.

(A quick note for people familiar with this. One might think that this variability is all down to the funny bank holidays we had in 2023, this particularly impacting the first few days of the month, and so bringing up an apparent variability that really only applies to those days, but doesn’t “infect” the rest of the figure. Nah, take a look at the same thing but looking at the share coming from more than two months back. It’s still all over the place.)

And all this is monthly. The weekly figures will be far higher than any of these, and likely also more variable (unfortunately, the ONS do not share them directly, so we can only infer).

So what’s going on?

Very roughly, very crudely: since the start of 2023, the “backlog factor” in death registrations has jumped to a sky-high level and is still jumping around like a mad thing. We can’t see the weekly factors, but the monthly patterns give an idea.

As a result, when anyone looks at a weekly registration and compares it to a previous year, almost all of what they are looking at relates to how successful the system is at catching up with a set of registration delays and backlogs that have been building for a while, and became especially acute since 2021. To roughly size this effect, one can see from the chart that the variation is of the order of 5-10% of the total deaths registered in a month, which is worryingly comparable to the excess death rates we’re seeing in 2023.5

And all this is true no matter how sophisticated the analysis is - whether it uses age-standardised death rates, whether it uses 2019 or a 5 year average as a baseline, with a trajectory or not. The excess death patterns being displayed are (mostly) not excess death patterns, they are registration delay patterns. We need to be using occurrence date data and just take the penalty on timeliness - there is little value in being misled faster than anyone else.

Oh, who cares?

But then, finally, why does any of this matter to people who don’t get paid/their kicks from looking at this stuff?

Very simply, we still don’t know what caused the (absolutely, definitely) real excess death patterns we have seen since Q2 2021. We have theories, and given that we are talking about hundreds of deaths a day, we urgently need to determine which of these theories is the right one (or, more likely, the right ones) - only then will we have a hope to fix them. Current attempts to be timely on death registrations are doing this at the cost of mis-stating when these deaths actually happened. And this means we are likely to look to the wrong causes and address the wrong factors, muddying the waters, and making it less likely we will be able to address the issues themselves.

Yes, I think this has a lot to do with NHS pressure, specifically on emergency care - and the waits that spiked with an identical temporal pattern - but we’re talking about something else at the moment.

It’s worth noting that I have a slightly different preference on baseline than Jean’s, so my “occurrence date” one would slope slightly more upwards and end a touch higher than his, but this difference is small compared to the main point.

It would be simply lovely if they did.

In 2020, this date varied a bit, but from 2021 onwards, they just went with “deaths registered by the 7th day of month x”

To be clear, I don’t think 2023 excess deaths number is zero. Even occurrence date approaches show a consistent positive excess death rate. But I think it’s roughly half the cumulative number the registration date methods are giving at the moment.

Thank you for this analysis Paul.

I know CMI (and ONS, though I can't speak for them) are aware of this risk. CMI mortality monitors include a caveat "Our calculations rely on data for registered deaths, and we are conscious that during the pandemic deaths may have been registered earlier or later than in previous years. Consequently, comparisons of mortality between years during the pandemic and earlier years may not be on a like-for-like basis."

It is only recently however that analysis (including yours and work by Jean Fisch) has made it clear that this is a very likely explanation for some of the recent excess - i.e. the theoretical risk looks like it has become an issue.

I have made sure that relevant people at CMI and ONS are aware of this analysis.

I am a bit confused about the late registrations, my dad died in march and it was practically the first thing we had to do