MMR and measles

Not again, please

One of the few good things about COVID is that its effects seem to be mildest in young children. There are some tragic exceptions, but - in the majority of cases - under 10s suffer very little harm.

Measles does not show any such mercy. It is violently contagious, with an R0 of 12-18 (probably) and its age-fatality link runs the opposite way to COVID: it kills young children by preference. The chart gives a recent (2023) estimate of the global case fatality rate by age, for low and medium income countries.

Note that these most recent numbers for measles are for LMICs, simply because there are so few recent cases in high-income countries. There has been a cheap and effective measles vaccine available for years, and when a country keeps uptake strong (95%+) sizable outbreaks simply do not occur. So fortunately, it’s very hard to estimate case fatality rates in rich countries with good healthcare systems - though we can hope they will be a good deal lower than in LMICs.1

Olivia Dahl

More striking than any chart is Roald Dahl’s unbearably stark recounting of the death of his daughter, in 1962.

Olivia, my eldest daughter, caught measles when she was seven years old. As the illness took its usual course I can remember reading to her often in bed and not feeling particularly alarmed about it. Then one morning, when she was well on the road to recovery, I was sitting on her bed showing her how to fashion little animals out of coloured pipe-cleaners, and when it came to her turn to make one herself, I noticed that her fingers and her mind were not working together and she couldn’t do anything.

“Are you feeling all right?” I asked her.

“I feel all sleepy, ” she said.

In an hour, she was unconscious. In twelve hours she was dead.

The measles had turned into a terrible thing called measles encephalitis and there was nothing the doctors could do to save her.

This letter is justly famous, and I suspect it will become even more so. However, it is not so often reported that the Dahl had been urged by his brother-in-law, Professor Ashley Miles, FRS - then head of the Lister Institute of Preventive Medicine, not to worry and “let the girls get measles … it will be good for them.” (from Patricia Neal’s autobiography, As I Am, 2010).

There was no vaccine available in 1962, but Professor Miles had provided a small amount of gamma globulin to the family - the best protection available at the time. There was enough for one, and the Dahls used it for their son Theo - who was already in poor health, needing a shunt for hydrocephalus - rather than the two girls.

Dahl was floored by grief for years afterwards, but he eventually wrote the piece above, when he became concerned about the number of parents not taking up the first vaccine, introduced in 1968. Rates climbed, and the vaccine was subsequently offered as part of the combined measles, mumps and rubella (MMR vaccine, introduced in 1988), whereupon rates climbed further. Both of these events are clearly visible in the long-term time series that you can trace when measles is made a legally Notifiable Disease.

A dark turn

The major developments in the years since then, are both well-known and terrible. The 1998 fraudulent paper and the resulting scare around the MMR vaccine is too dreadful to recount once more, but it’s worth pausing to note three publications that have never properly apologised for the damage they did:

The Lancet - which published the original 1998 paper, despite its obvious conflicts of interest and poor methodology, then for more than decade refused the requests of 10 of the 12 authors to retract the paper when subsequent research found the results to be unreliable, and the lead author to have concealed strong financial interests.2

Private Eye - which published inaccurate wink-wink article after article, culminating in a 32 page scaremongering supplement in 2002, all based on the fraudulent Lancet paper.

The South Wales Evening Post - which ran a series of scare stories about vaccines in the late nineties, after which MMR uptake in Swansea fell as low as ~67.5%, and took decades to recover. The same paper then exaggerated the scale of the subsequent measles outbreak, which occurred in 2012.

The only one of these three that seems to have tried to learn anything at all from the disaster was Private Eye, who commissioned their “MD” columnist Dr Phil Hammond to review what went wrong in 2010. It is particularly notable that The Lancet has done nothing similar, despite the editor responsible for all of this never admitting error, and still being post today.

To the present day

Now all this is history…

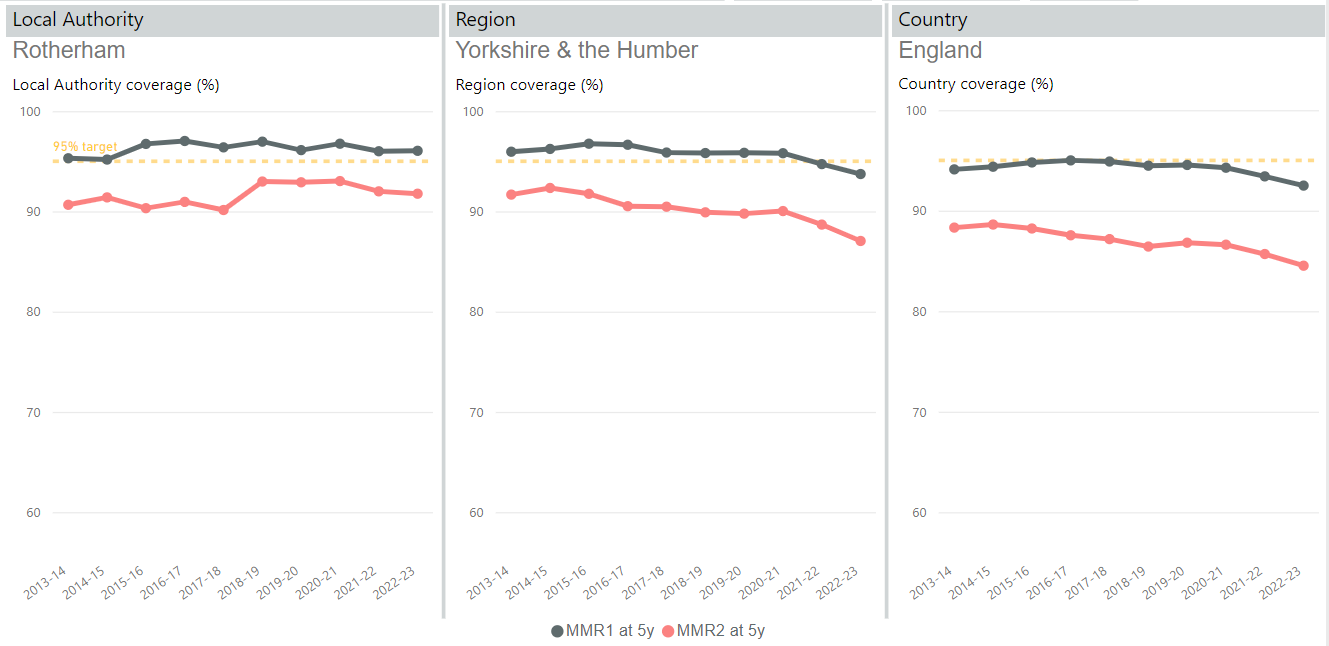

… which we, appallingly, appear set to relive again. Because of the numbers on this chart.

This is uptake data amongst five year olds, from the COVER programme (with some selected authorities labelled) which gives quarterly updates on coverage levels of all childhood vaccinations, including the first and second doses of the MMR vaccine, which all children will have been offered (the first at 12 months, the second at 3 years 4 months).

The point here is that with an R0 in the double-figures, there’s very little we can do against measles outbreaks, apart from vaccination. We need to keep rates high (ideally two doses at 95%+) to retain true herd immunity and stop outbreaks before they can get anywhere. Treatments are imperfect, NPIs are pretty much powerless against an R0 of 12+; it is almost entirely vaccination that keeps us - and especially young children - safe.

Focusing on Hackney - a particular outlier3 - we can also see that several of the more obvious factors behind that might be thought to be behind recent low rates, are almost certainly irrelevant.

As for why this is happening, there looks to be a lot of “inference to the most attractive explanation” going on. Those blaming public distrust stemming from (non-existent) vaccine mandates for COVID, are just being lazy. It is obviously not driving the main trend, which started around 2014, and and the drop is massively concentrated in a few localities, most obviously in certain boroughs of London.

Likewise, while it’s tempting to blame the louder and more stupid of the current wave of anti-vaxxers: the never-knowingly-numerate columnists for British weekly political magazines or bizarrely race-obsessed US Presidential candidates, their influence doesn’t fit the data at all. However idiotic and obnoxious they may be (and they are both) - they are unlikely to have disproportionately large audience in Haggerston, but not - say - in Rotherham.

Instead, the factors making a real difference appear to be demographic, and in particular have an ethnic component. We know that immigrant groups have very low trust in government in general, which correlates directly to vaccination hesitancy, especially for their children. And this appears to be a major factor in the low rates we are seeing in London boroughs. We saw this effect with the COVID vaccines, where Afro-Caribbean and African-origin ethnic groups had particularly low uptake rates compared to all other groups, and the effect appears to be even stronger and more striking when we come to children.

Here is Hammersmith and Fulham (one of the London boroughs close to the bottom of the chart above), which released a report on the worrying trends, and split its MMR take-up by self-reported ethnic origin (this data for 2021).

Careful study is needed to separate out effects such as deprivation and education levels, but once you do the best you can, the same strong correlation remains: African and Afro-Caribbean groups tend to have the lowest take-ups of all major childhood vaccines, including MMR; White, Chinese and Indian show the highest, while others are less consistent: e.g., Pakistani and Bangladeshi rates appears to vary by study and by vaccine.

This is tricky: it suggests that the trend is down to factors such as trust in government falling in these groups, and this can only be addressed carefully and locally. Yelling at people to join in a national top-down programme is unlikely to work.

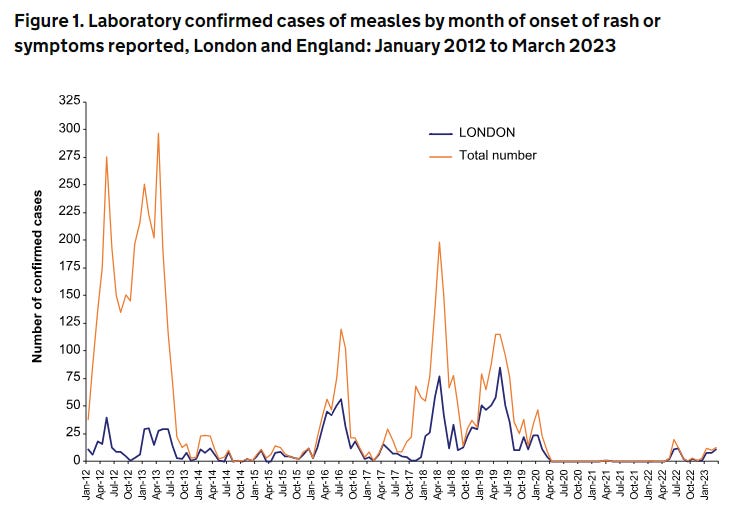

Given we are falling well below uptake rates that are needed to keep such a contagious disease as measles suppressed, the obvious question is when we might expect an outbreak to occur. Unfortunately this appears unpredictable - in Wales, where the most recent UK outbreak occurred, there was a nearly a decade-long delay between the point at the the MMR rates started getting dangerously low (24 month 1-dose rates were at ~67.5% in Swansea in 2003, as mentioned above) before the major outbreak finally occurred in 2012 - around 1200 cases, where - fortunately - only one person died.

We’re already at Swansea-like rates in Hackney and other London Boroughs (Camden, Islington and Haringey are also particularly low), but it would be outstandingly stupid to rely on a similarly decade of lag. There will be significant travel to and from regions where measles is endemic - much more than there was to and from Swansea, and I have not seen convincing reasons why the outbreak did not occur sooner there.

Indeed, so far as I can tell, the Swansea timing appeared to be puzzlingly long, and quite likely down to luck. While we might fairly confidently anticipate a London outbreak if these levels of vaccination continue - and it appears fairly easy to predict where, almost to within a few miles - I doubt there is any reliable way of saying when.

It is notable that in the last set of data we have (January - March 2023) laboratory cases of measles remain reassuringly low. But, in contrast to historical patterns, they are all in London.

The good news is that all this appears very fixable, well before it occurs. The Swansea outbreak was serious, and had thousands of cases, but it was brought under control in a matter of months, using only standard but targeted MMR vaccination. Even with the outstandingly short-term outlook of the current government, the cost to the NHS of extra vaccination drives in some local areas alongside some hard outreach work will be massively, massively favourable when compared to the costs of a major measles outbreak.

The public health authorities now have a clear run at this, as COVID vaccination drives are diminishing in intensity; and are on their way to being combined with the seasonal flu campaigns. Also, compared to 1998, we are in a much better position on data, and with many of the more damaging charlatans being largely recognised for what they are (though one might doubt - say - The Spectator ever had a massive circulation amongst African and Afro-Caribbean communities in Upper Clapton).

Unlike other looming risks such as avian flu, or some new strain of COVID, we know pretty much precisely how to stop this one: it’s hard, sustained community-based work. But not in any way optional.

The smaller sample for Central and Eastern Europe alongside central Asia, gives an idea of what this might be: of the order of 0.5% in the younger ages. We should do still better in a UK context, but of the order of one death of a young child per thousand cases does not appear unreasonable.

The Lancet held out until 2010, finally noting a full retraction of the paper in a small anonymous paragraph, after overwhelming evidence of fraud for monetary gain was collated and published by the indefatigable Brian Deer of the Sunday Times, and when the lead author was just about to be struck off as a doctor by the GMC.

This astounding inability to admit error, even in the face of overwhelming evidence, was only matched a few months later by the same editor’s use of the pages of the Lancet for a fact-free, rhetorical defence of Roy Meadow in 2005, after he was found guilty of severe professional misconduct by the GMC.

There may also be denominator issues: listing more 5 year olds than there actually exist and so suppressing the vaccination uptake to lower than its true value. This is especially true given that Hackney is listed together with the City of London, which is a particularly odd area in terms of “residents”. However, this cannot be the whole story: the one-dose share, and the trend cannot be reproduced by this explanation.