Physics rests on a bunch of quantities called fundamental constants. As the name suggests, they’re very important and also don’t change, so people spend a lot of time trying to measure them to increasing levels of accuracy. As a result, as technology improves (say from the 1950s to the 1970s, when the invention and improvement of atomic clocks turned out to be particularly important), we see better and better measurements of values of Planck’s constant, the fine structure constant, the charge of an electron and so on.

We’ll take 1975 as the end-point, just because the changes after this tended to be relatively small.1

But before looking at how the measurements of these constants evolved over time, it’s worth first thinking how they “should” have evolved - that is, if we didn’t have messy, complicated humans involved.

If the experimenters were merely working with a variety of random errors (imperfect equipment, errors in the set up, random noise from external disturbances and the like), you might expect to see an evolution over time that looks something like this:

Where the vertical lines show the stated uncertainty levels. That is:

the modern value is always within the uncertainty bars (i.e., the experimenters recognised how far they were likely to be off)

the “true” modern value was approached from both sides in a kind of random scatter - they were likely to be off on each side regardless of the other points.

What actually happened is much more human.

Planck’s constant:

Fine structure constant (inverse):

Charge of the electron:

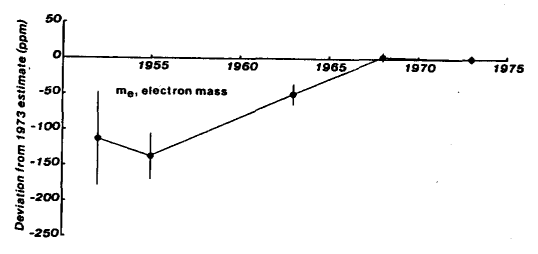

Mass of the electron:

Avogadro’s number

The numbers don’t bridge around the modern value - they tend gradually towards it from where they started.

And the error bars on the early values are always too small. With the exception of the fine structure constant, where it’s pretty close, they tend to be a fair way off the “true” (or at least, the modern) value - while they very often overlap with the “last” value that was given.

Something fishy is going on.

(Source: Henrion and Fischhoff 1985)

There’s been a great deal written recently about scientific research integrity.

Much of it has focused on what appears to be deliberate fraud - apparently motivated for monetary or status gain within a scientific (or - in the case of behavioural economics - pseudo-scientific) field.

I suspect that this kind of outright fraud: just making up data, is much more widespread than we’d like to think. Given the incentives to publish striking results, and the demonstrated failure of the peer review system to catch deliberate fraud, I cannot see how it can be otherwise.

And it’s noticeable that the fields apparently most riddled with fraud, as measured in terms of retracted papers (e.g., anaesthesiology, behavioural economics) are in those few fields where there are small groups of people active in seeking it out and catching it. Which rather suggests that it’s everywhere.

But for my money, the the patterns above are different. They are not the result of outright, or deliberate fraud. Instead, they were produced by teams trying their very best to get the best results, and taking every precaution to do so. They are evidence of something even more prevalent to science: someone consciously, or unconsciously, trying not to look like too much of an idiot.

In a nutshell, when you’re doing something hard, it’s really hard to avoid being pulled in the direction of things that “look right”. It takes a lot of time and “feel” to get a difficult piece of equipment working. You don’t even bother to record results until they’ve stopped looking obviously wrong. You don’t want to look like the incompetent who can’t even get their equipment working. But you get your sense of what’s obviously wrong - at least partly - from the result you already know. And then you correct for estimated errors: temperature, resistance effects - you don’t want to look like an idiot. But when do you stop correcting, and when do you stop searching for more things to correct for? It’s a matter of judgment. Again, you stop when things “look right”.

And that’s at least one reason we get that invisible magnetic “pull” of the past results, tugging the new reads back towards what was “known” to be right before, and away from clustering around the “true” value.

The positive thing is that - in response to phenomena like that noted above, fields such as physics have developed techniques for combatting these biases. They are collectively known as “blinding” techniques, where you deliberately obscure the “known” result that you are seeking. In areas like medicine, you do this by simply not telling anyone (not the doctors, nor patients) who’s getting the real treatment, and who’s getting a placebo. In physics, you have to be more creative.

I heard about a particularly simple and beautiful approach a little time ago when I went to a talk by Eric Cornell, who outlined the results of a 14 year quest from him and his research team to measure the electric dipole moment of the electron - a similarly fundamental quantity to those we saw above.

The electric dipole moment of the electron basically measures how “off-centre” the charge distribution of the electron is (that is, is there an offset of where the charge is distributed in an electron, versus where its mass is distributed?). This is important, because if such an offset does exist, it might give a clue as to the source of the primordial asymmetry that favoured matter over anti-matter.

The trouble is, blinding data is very difficult in this case. Everyone knows the “anchor” value. It’s zero. And there will be an unconscious bias to adjust things until it “looks right”.

In the talk, Professor Cornell outlined the main points of their method (HfF++, plus a shed-load of lasers), and then showed a chart of their raw data which led to a few intakes of breath from the audience. The chart clearly showed readings converging to a non-zero value.

Having had his little joke, Cornell came clean. The group had done something clever. At the outset of the experiment, they asked their data-logging computer to generate a single constant value and keep it secret. Then to add that constant to every value it reported.

They set up their experiment, tuned it and collected their data, always adding that secret value to everything. Now they had no idea what the value was they were “meant” to be seeking.

Finally, after several years of work (they could only get their kit working about an hour per week) they got to a point where they were happy enough with the data that they had to go ahead and publish.

Then, and only then, they asked the computer to subtract the value off again.

Quite an emotional moment. This picture is from a few minutes later.

(Source: JILA)

Their data was indeed consistent with zero and limited it to be smaller than 1.3×10^−28 e cm which, (in conjunction with a similar result from a Yale-Harvard team) killed off a fair number of speculative theories in particle physics.

It’s a promising signal that it is possible to develop these kind of techniques to fight unconscious bias, and also that the social structure and professional standards of physics is strong enough to see that they are implemented (at quite some cost) for particularly important experiments.2 I suspect that it is pointing the way to the future.

My guess is that as the incentives to “massage” results into publication-ready form ratchet up and up, the normal cosy understanding that nice people don’t fake results - either consciously or unconsciously - will be seen as increasingly untenable.

Instead, any field which wishes to continue to be seen as “scientific” will need to implement “blinding” type approaches, alongside their analogous guardrails against more deliberate fraud.3 It will be seen as important as peer review.4

The costs of implementing these may appear high, but looking at the outputs of some fields today, the alternative appears to be growing cynicism amongst practitioners, and the public. We are getting to the point where new results are simply being ignored, at least before extensive replication and checking. And this is rational - in many fields, a Bayesian approach working off past experience will tell you that a new striking result is likely to reflect anything out there in the world, than it is to have been worked into being by a mixture of wishful thinking and outright fabrication. It is not surprising that people act accordingly.

As a result, any reputable journal should now be demanding that some of the weight of these checks and replications will increasingly happen before publication, not after. Behavioural economics in the early 21st Century may find its place as a cautionary tale.

And because that’s what I’ve got the charts for.

In my - speculative - view, such guards against our tendencies to reason like humans, are part of what defines a field as a science, rather than just another field of enquiry. That is, they are part of a “demarcation criterion”.

For example, mandating that psychology experiments have been performed by at least two independent groups, and their results kept separate from one another until each group have analysed and interpreted the results, after which they are published as a joint paper with discussion on any discrepancies.

Or, given that peer review has shown itself utterly incapable of detecting research fraud - cases are caught after publication, not before, it may quickly be seen as more important.

Excellent piece. I’d add only that while your point about error bar size is well taken, in many of these cases the fact that the values are all over (or under)estimates is because of the nature of what’s being measured. To use an astronomical example, no one who ever tried to measure the speed of light underestimated it, as when you’re measuring something fast you’re much more likely to make an error in one direction - the precision of what you’re timing will tend to lead you to overestimate a short interval.