Every year in England and Wales, a cynic1 might describe a process like this:

Around spring, the incumbent government / devolved government promises that they are working hard to fix NHS capacity before next winter.

In summer, the relevant NHS bodies warn that nothing meaningful is happening on the ground and/or everything’s much worse, and they are in no way ready for the winter.

Through October and November we watch nervously as ripples of seasonal respiratory infections (e.g., RSV, flu and now COVID) grow into waves. The NHS know what’s coming and try to vaccinate as many of the old, young and vulnerable as possible.

As winter progresses, wards fill up with patients, so A&E is unable to admit patients to the hospital, so A&E fills up, so ambulances are unable to transfer patients safely to A&E, queue at the front door and so are unable to respond to new calls. Patients suffering from heart attacks and strokes wait hours for help, and incur enormous harms - enough to show up in excess death indicators.

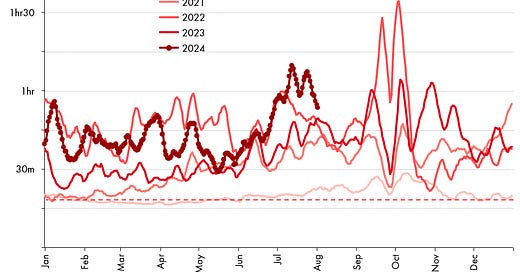

In late December or early January, the waves of RSV, flu and COVID peak. If they all are high and peak at the same time, you get the winter of 2022 - when we saw a monthly average response time to stroke/heart attack symptoms of 1 hour 32 minutes. If, by luck, the peaks of infection are lower, or offset from one another, you get the winter of 2023 - average response time 45 minutes. The target response time is 18 minutes.

The waves recede in January and February, the NHS cares for the survivors and we bury the dead.

Go to 1.

Welcome to winter 2024/5

Right now, in 2024, we are currently somewhere in the transition between Steps 3 and 4. Ambulance response times are - once again - acting as an indicator of the overall pressure on hospitals: all the pressures pile up at the front door, and they are stuck parked there, unable to unload and cannot get back to pick up new patients. Adding more ambulances makes the queue a bit longer, but does not change much else.

“Sticking plaster” solutions such as changing protocols so that ambulances do not need to transfer patients to an A&E bed, but instead cram them into “corridor care” so they can go and pick up the lady with the heart attack from her kitchen floor … are in train. But the fundamental issues remain.

For 2024, any new investment does not have any time to make a difference, we are pretty much set in to suffer through steps 4-6. Really, the only two questions left now are “just how bad?” and “where will it be worse?”

First, how bad is it likely to be?

October ambulance times have just come out, and they suggest we are looking at a 2023-like trajectory, if we are lucky.

Or, more clearly to compare years like-for-like:

Not the worst, but fully in the post-pandemic trend of overwhelmed NHS capacity, not getting anywhere near the 18 minutes target. If we put this trajectory so far, alongside measures in the NHS England respiratory virus tracker, we wonder greatly whether flu’s prevalence at this time presages a higher peak than last year, and whether COVID could come around for “another go” before Christmas. If either or both of these things happen, things could get worse. If they do not, we might keep things down to a 2023-ish level.

So, while it’s not entirely clear, what the out-turn will be, what is clear that the system has not been fixed, and - yet again - it is up to external, uncontrollable factors on just how bad it will get.

Where will it hit worst?

As for “where”, then in the last few years, this has been blindingly obvious. It’s always been worst in two places: in the South West of England, and in Wales (particularly in Swansea Bay).

But this year, their unenviable crown is being challenged in the worst possible way. By the Midlands.

Looking, for example, at East Midlands ambulance service response times, and going month-by-month, we can see in this area 2024 is already starting to look more like the winter of 2022 than any other year. This is unique amongst the ambulance services, and even in absolute terms, the East Midlands response are currently tracking longer than the South West. This does not often happen.

Of course it’s down to the same things it’s always down to - the delays handing over patients at the hospital door. They are the worst in the Midlands than they have ever been at this time of year - something like this.

In particular, there appear to be problems mounting in a few trusts: Royal Stoke University, Kettering, Northampton General are each worth bringing out - but there are others too - all tracking with far worse times in the 2024 compared to previous years (and yes, even worse than in 2022).

Now, whether the Midlands will continue to see the worst pressure, and become a worse place to be seriously ill than even the historical “champion” the South West is rather a moot point.

The point is that people of the Midlands are tracking to see their worst winter yet, in terms of emergency response. If you’re vulnerable, consider whether you want to take up the free flu and COVID shots to protect yourself, and - though it’s completely unacceptable to need to think this in rich western country - you might consider planning ways to get to hospital in an emergency situation that does not depend on an ambulance arriving in a timely manner.

And … Wales

Unfortunately - again - I do not think that the Midlands will gain the dubious distinction of being the worst place to be seriously ill in the UK this winter.

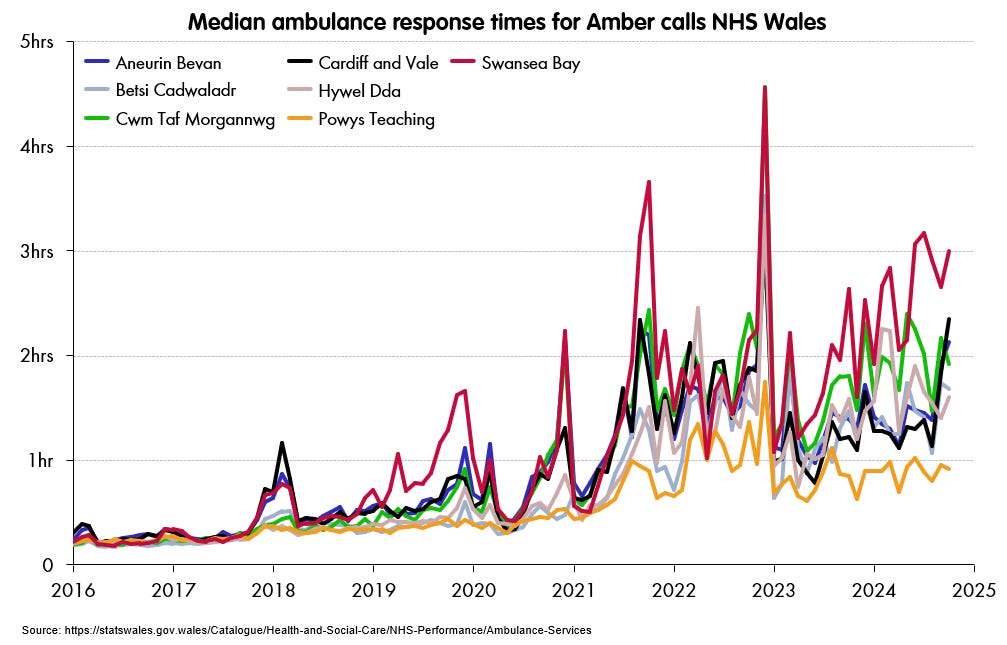

I’m afraid that Wales — once more — is looking worse and trending towards a full-on nightmare for 2024. Times are tracking far worse than last winter, and the latest read is already ahead of October 2022.

[Update: 27/11/24 - added with October 2024 figures]

Now, beware of comparing these times directly to the English ones. They are medians,2 not means, and the categorisation of Red, Amber and Green calls (the Welsh system) is somewhat different to the Category 1-4 system that England uses. Nonetheless, the Welsh “Amber” also includes suspected heart attacks and strokes, and gives rise to stories like the death of Dave Strachan in March 2022.

The extraordinary point - not brought out enough - is that Dave Strachan’s story is not at all unusual. To their credit, the numbers reported by the Welsh ambulance services are extremely detailed, so we can estimate exactly how many people there are like Dave, who report urgent, dangerous symptoms, and are still left waiting over nine hours(!) for an ambulance to arrive.

The most recent month: September 2024, there were 13,963 calls which were, like Dave’s, were classified as Amber priority. That is, they were not immediately life threatening (not breathing, bleeding out), but still a proper full-on emergency: for example: symptoms consistent with a heart attack or stroke, where delay is likely to cause considerable harm.

The 95th percentile time is a decent measure of “how bad does it regularly get”. It is the lowest time in the worst 5% of delays. And for these “Amber” calls across Wales the 95th percentile is scarcely believable: 9 hours 4 minutes 48 seconds.3

Which means across Wales, roughly 700 people per month - 22 per day - are experiencing the kinds of delay that Dave Strachan did. Perhaps not all of them would have had symptoms quite as bad as Dave’s, but enough to be categorised as Amber.

Dave Strachan’s story is remarkable simply because it is so horrific and yet - still, apparently without comment or consequence for the Welsh - or for that matter the UK - administrations,4 is happening multiple times a day.

Not me, obviously. A cynic.

Medians are typically lower than means for ambulance response times, so this actually makes Wales look better than it should.

One can compare these with England’s 90th percentile times for Category 2s and 3s. There is a fair amount of wriggle room within the comparison, but not enough to avoid a conclusion: Wales times are considerably worse than England’s. Which in turn are considerably worse than Scotland’s. UPDATE: figures given were for September 2024 - the latest available at the time of writing. October 2024 has just been released and is still worse at 9 hours 42 minutes and 41 seconds.

The last few Welsh Government Health secretaries were Mark Drakeford, Vaughan Gething and Eluned Morgan, being the post they held they each ascended straight to First Minister.